Lucy: Correcting Congenital Ectopic Ureters

HISTORY:

Lucy, a 5 month old female Corgi presented to me for constant urinary incontinence. She could urinate normally outside but would often dribble urine and leave large puddles while resting. She had been evaluated by her primary veterinarian for a urinary tract infection and sent home on a trial of antibiotics and phenylpropanolamine (Proin). Unfortunately, these only partially helped, and she continued to be incontinent.

PHYSICAL EXAM and DIAGNOSTICS:

On exam, Lucy was a playful and happy puppy. She had evidence of urine scald and malodorous urine on her hind end. The rest of her exam was normal. A urinary ultrasound revealed mild left pyelectasia and mild left ureteral dilation which could not be definitively traced. A normal ureteral jet in the trigone was only identified on the right side. CBC, chemistry and urinalysis were normal; her urine culture was negative.

TREATMENT and OUTCOME:

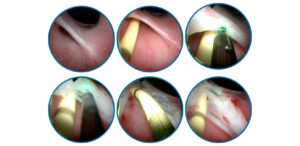

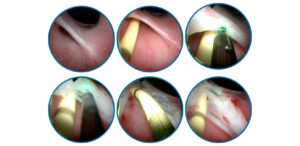

Based on these findings, it was decided to pursue diagnostic and potentially interventional cystoscopy for Lucy. Her right ureter was in proper position in the urinary bladder, but the left ureter was seen tunneling through the wall of the urethra and entering mid-way down. This explained the incontinence as the urine from the left kidney would bypass the sphincter and not be stored in the bladder for intentional urination. A Ho:YAG laser fiber was used to perform a cystoscope-guided laser ablation of the unilateral intramural ectopic ureter. The left ureteral opening was repositioned to equal level with the right ureteral papilla. A vaginoscopy revealed a thin paramesonephric remnant of vestibulovaginal junction which was also ablated successfully with the Ho:YAG laser.

Lucy recovered uneventfully from anesthesia and was discharged that afternoon with carprofen and amoxicillin for 3 days. The owner was instructed to continue the previously prescribed Proin. One week after the procedure, Lucy was completely continent with no accidents. The owner stopped Proin, and she is doing well at the last update from the owner 1 month after the procedure.

DISCUSSION:

Ectopic ureters are a common congenital abnormality leading to partial or complete urinary incontinence in young dogs. It happens most frequently in female dogs with a breed predisposition including Huskies, Retrievers, Poodles, terriers and Newfoundlands. Dogs with this abnormality frequently have other congenital anomalies, such as USMI (85%), renal dysplasia (40%), hydroureter/hydronephrosis (25%), shortened urethras and persistent paramesonephric remnants.

There are multiple methods for correction including surgical reimplantation of the ureters or cystoscope guided laser ablation. For those with the less common, extra-mural version of ectopic ureters, surgery is required for correction.

The diagnostic method of choice for evaluating dogs for ectopic ureters is cystoscopy. This allows us to diagnose and treat under the same procedure in a minimally invasive approach. It is important to remember that dogs with ectopic ureters can have normal or subtle changes on ultrasound or contrast pyelogram studies. When there is a young dog with incontinence, we always recommend cystoscopy as the next step.

Since dogs frequently have other congenital abnormalities, neither surgical correction or cystoscopic laser ablation are not completely effective. While the literature varies, a simplified way to remember outcomes is that 1/3 will be completely continent post procedure, 1/3 will be continent after the procedure and addition of medications, and 1/3 of pets will require further procedures such as urethral bulking agents or urethral sphincter hydraulic occluder placement.